This is the talk delivered by George Murray at the International Aphorism Conference in Wroclaw, Poland on October 25, 2025. George is a Canadian poet, teacher, and editor. I’ve blogged about his aphorisms here and here. —JG

My talk today is about how I see the poetic aphorism as differing from the philosophical aphorism, but also how the form creates a bridge between the two intellectual endeavours. In order to get where I need to go with this, I must to give you a bit of my history with the form.

I wrote my first (intentional) aphorisms in 2008. The year before, I had been invited to speak at Princeton on Canadian Poetry, and the organizers planned a public reading for me as a poet. I was paired with James Richardson (scroll down for blog posts about Jim’s aphorisms here and here —JG), a venerable and much-beloved American poet and aphorist, and then-head of the Creative Writing program at Princeton.

I read from my recently released book of sonnets that employed an unusual form – “rhyming” ideas instead of sounds as its formal constraint. So, for instance, a word like “night” could rhyme with a synonym like “evening” or an antonym like “day” or homonym like “knight” (on a horse) or even an anagram like “thing”. This had garnered a lot of attention in the Canadian poetry world.

But it wasn’t this innovation that interested Richardson. After the reading, as Jim and I sat at a local pub, he commented on the closing couplets of my sonnets, saying something like, “Your poems often seem to end on an aphorism, as if you were writing up toward them. You should look in your journals to see if you have more little nuggets you haven’t yet put into a poem.”

Who was I to argue? Richardson was one of the few North American masters of the poetic aphorism, and at this point, I’d never even heard of them at the time. I had always thought of the aphorism as a philosophical form.

So, once back in Canada, I looked through my motley collection of scribblers and moleskins and found not dozens, but hundreds of aphorisms. These were little thoughts that had weight and depth but had somehow never found their way into a poem. In total, there were nearly 1,000 of them scattered through decades of old notebooks.

I subsequently published two books of aphorisms, Glimpse and Quick, in 2010 and 2017 respectively. Both have sold well in the Canadian book market – a market that typically doesn’t respect or value poetry as a commodity worth paying for. Canada is a place where selling 500 copies of a book of poems is considered a successful run, and I am lucky enough to sell well, but these books of aphorisms were selling more. In fact, because there is no poetry “Bestseller Lists” in Canada, my first book Glimpse made it onto the bestseller list in one paper under the “fiction” category. (I found this funny, that a book of “truths” would be listed under fiction.)

Why is this, I wondered? Why do well-crafted and thoughtful poems not spark the imagination of the public in the way aphorisms do? It’s easy to say that poetry can be difficult for those that grew up only encountering it in school, or that the form feels archaic and irrelevant to the current milieux, or even that we live in a time of sound-bites and tweets and abbreviation that already mimic the form of the aphorism, but is that truly what’s going on?

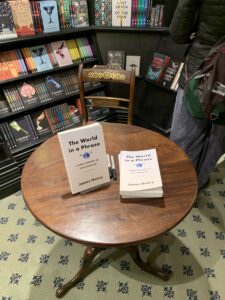

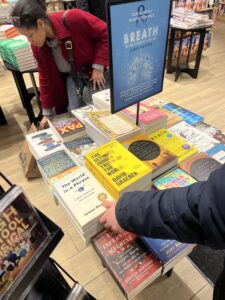

Some people, like our keynote speaker James Geary, see the aphorism also as a vehicle for delivering those philosophical “deep thoughts” to casual readers in a friendly manner. In his interview with the Harvard Gazette dated Oct 10, 2025, James asserts that aphorisms must make you think, but that they also “have to be super accessible; you can understand them in a second.”

I see what he means, and I think I agree, but I come at the whole endeavour from another angle – a poetic one. One that is used to allusion, nuance, and multiplicity of meaning. So yesterday when James said that the aphorism must be “effortful, not effortless”, I thought, “Aha, now I see what he means. And we do agree.”

For me, poetry is, at its core, an art anyone can practice, but not all can master. Just as anyone can become an apprentice carpenter, learning the tools and tricks of that trade to plane and cut and join wood, so too can anyone become an apprentice poet, learning to hide and reveal, join and break, state and allude in order to elicit epiphany on the part of the reader. And just as with poetry, not every carpenter can go on to greatness as a fine artist in cabinet making or turning or other wood working. Most remain merely serviceable workaday craftspeople.

Even so, every person in this room, in this building, in this city, in the world, has had the experience of epiphany. A sudden dawning. A realization. A poetic moment – those moments of profundity where thoughts come unbidden about the meaning and scope of life as we know it. Maybe they’re sitting looking at a sunbeam from their window and watching the dust motes float about, and thinking, “There’s something here. Something important at the edges of my consciousness.”

The major artistic difference between them and a poet like me is, I’ve spent 30 years training myself to recognize such moments, and to capture them as quickly and elegantly, as possible.

As a poet, when I have a moment like this, I roll it over in my mind, make my hasty notes, and later, when fleshing them out, I lay down layers of craft and form.

See, the initial trick with an epiphany is to realize you’re having one. After that, it’s a race to capture its beauty and meaning before it begins to decay in your mind. A scramble to write it down as faithfully as possible but then slowing the process down to really examine it and flesh out its levels of meaning and nuance.

This is all part of the hopeful endeavour to elicit a similar epiphany in the mind of the reader, to convey my wonder and thought, and to make the poem sing. I take an idea and illuminate it, not unlike a medieval manuscript. My goals are elegance and beauty, but also a satisfying and allusive complexity. I want to create something that flows and has grace on the tongue but also offers a deeper level for those willing to explore it.

That said, I feel no special obligation to “accessibility”. I subscribe to the idea that poetry worth reading is poetry worth rereading.

In the end, the aphorism works differently for me. It arrives as a statement that immediately tells me the rest of the “poem” is unnecessary. This doesn’t mean it’s whole. It may require editing and crafting, but it can be perfected without the flourish and linguistic fireworks common to poetry. Aphorisms are worked on – pared down, added to, crafted, like a poem, but they need no poetry around them to sing. They use the tools of poetry, like metaphor, metonymy, imagery, play with idiom and cliché, etc., but they do so economically and succinctly.

A few examples (All from Glimpse, ECW Press, 2010):

Rubble becomes ruin when the tourists arrive.

As with the knife, the longer the conversation, the less frequently it comes to a point.

Anyone who yells loud enough can be famous among the pigeons.

Until quite recently, I explained aphorisms to the uninitiated as “poetic essences” – by which I mean, they are “poems without all the poetry getting in the way”. A poetic essence, I held, is a thought or epiphany or idea that requires no more elaboration than the statement itself, yet it is still a poem.

An aphorism is not always a simple thing, or an uncrafted thing, in that over time it is laboured over in equal measure to any of my poems – but it is a whole piece that requires no further lyrical exploration to convey the totality of its meaning and elegance.

In a sense, the poetic aphorism can be seen as the “core” of a poem that never was and needn’t ever be. It does the work of a poem, in that it offers the chance of epiphany to the reader willing to reach for it, but it does so in a more direct way, eschewing the layers and nuance of poetry in favour of efficiency and a more direct clarity of meaning.

A good poem, I tell my students, is one that can be read many times in many ways without losing its appeal. It has layers of meaning that reveal themselves on second, third, fourth, and so on, readings. An aphorism, I say, and as James writes, can usually gloss on the first read, meaning it gives up the goods quickly and directly.

Yet, for a poet – or at least for this poet – I have come to realize that is not entirely true. In writing aphorisms as a poet, I can’t help but concentrate on adding back in the nuance and layers of meaning while also offering efficiency and clarity.

I want my reader to grasp the idea of the aphorism on first read but find other layers as they return to it later. I want the reader to stop and say, “Huh” when coming to the piece a second time. I want the language to offer multiplicity instead of uniformity of vision, which seems somewhat antithetical to the nature of the form.

As with poetry, I don’t think requiring a reader to reread for a fuller understanding is a negative. I see it as a positive – an element that extends the value and life of the piece.

More examples (From Glimpse, ECW Press, 2010):

The body is what happens when the mind wanders.

Panic is worry on a tight schedule.

Dirt is what we heap upon enemies; loam our dead; earth our children.

This forces me to ask myself: Are my poems then just aphorisms that are overwritten? I’ve checked. Some of them are.

In many cases, you can reduce a poem to a single line or two outlining its essential meaning. Like what we call an “elevator pitch” for a poem – a direct statement against the poem’s coy play. But with most such distillations, the nuance and elegance can be lost. In the end, the poem requires poetry and poetic investigation, while the aphorism can employ the tools of poetry, but doesn’t require it.

I know this because I find that some ideas really do arrive fully formed, already an aphorism – announcing themselves as such on their way through the mind’s front (or back) door. They feel complete on arrival, even if in need of editing and craft – like flowers that skip the stage of the bulb, heading straight to petals.

In the same way a good short story can do the work of a novel in 30 pages, a good aphorism should be able to do the work of a long poem in one or two lines.

To illustrate this, in my second book of aphorisms, Quick, I even tried to take well-known longer poems and reduce them to a single thought. This resulted in varying levels of success. Many of the more spectacular failures were not included. These poems were too tangled or unsure of themselves or diverse in subject to distill.

Through this experiment I learned one can never capture all the nuance and allusion of poems of that scope in an aphorism – but one can focus on a single, pervasive idea, and craft an aphorism from it.

Examples (All from Quick, ECW Press, 2017):

TS Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”:

The mind’s cacophony is caused by the same thing as the city’s: crowds.

Alan Ginsberg, “Howl”:

The lamb that hears the growl needn’t stick around for the howl.

Margaret Atwood, “This Is a Photograph of Me”:

In a world made of surfaces the only place to hide is in depths.

Langston Hughes, “Let America Be America Again” (A poem-to-aphorism conversion which is particularly relevant right now):

A dream’s best intentions often end up a waking nightmare.

They allude to the source poem and even sometimes illuminate it, but overall lack the levels of meaning, focusing instead on a single layer and elevating it through the exclusion of other thought.

This is important because this is how aphorisms work for me. They are indeed poems without all the poetry getting in the way, but they are also thoughts without all the thinking getting in the way.

So, in the end, the sort of aphorisms I write are not in fact distilled poems, nor are they philosophical statements. They are their own form – separate from, but owing allegiance to, both poetry and philosophy. They evoke, allude, and refer as poems do, and they also tackle thoughts with depth and metaphysical importance the way philosophy does, all in the most economical way possible, but with grace, beauty, and nuance. I would pose a new term for their relationship to poetry going forward. Instead of poetic essences, I would call them “philosophical or poetic cores” or even “poetic allies”. They are not poems, nor are they really philosophy, but for me they are, at their best, both philosophical and poetic.

Thank you.