Be sincere, be brief, be seated.

Be sincere, be brief, be seated.

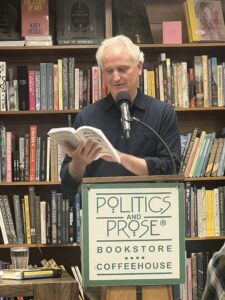

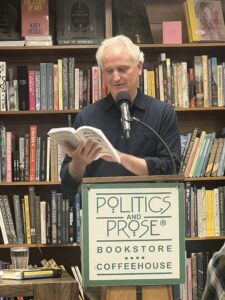

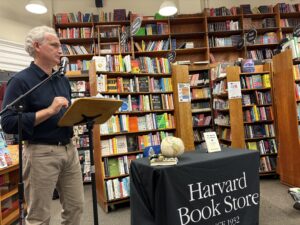

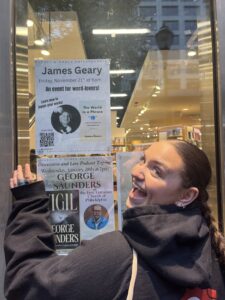

Thanks to the wonderful team at Harvard Book Store for hosting me and The World in A Phrase on Nov 10. And thanks to everyone who came out to juggle words, ideas, and balls.

There was a blank sheet selected from the globe, and the subject was: Anthropology. With a little help from everyone in the audience, I finally came up with something from Chamfort …

There are two great classes in society: Those who have more dinners than appetite, and those who have more appetite than dinners.

Fortuna stands some seven feet tall, on a pedestal overlooking seven Black automatons, in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Roberts Family Gallery. The mechanized figures in plots of obsidian perform a kind of ritual resurrection: One automaton, limbs flailing, repeatedly rises from and falls to the ground, summoned by another robot dressed in the robes of a prophet.

Fortuna takes it all in, periodically raising her arm and pointing to her mouth as an aphorism printed on a slip of paper pops out:

Your last shred of dignity is often your best.

Life is the abyss into which we deliberately and joyfully thrust ourselves.

Artists cannot be expected to follow instructions.

This diorama of suffering and redemption is Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine) by Kara Walker, an artist whose cut-paper silhouettes and installations have long engaged with complex issues of race, racism, and identity, as does this work. Fortuna the machine is also a contemporary variation on the crude mechanical fortune tellers once found in penny arcades. Drop a coin into the slot at the amusement park, and Zoltar or Madame Zita would produce a card with a prediction of your future on it. Fortuna herself may be a wonder of modern animatronics, but dispensing cryptic wisdom goes back to the beginnings of the aphorism and is one of the oldest ways we make sense of our world.

Aphorisms are the original oracles. Walker’s Fortuna connects today’s museumgoers with the people thousands of years ago who played the I Ching or consulted Pythia, the priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, for insights on the future and guidance on the here and now. The aphorism is, in some ways, perfectly suited to the digital age: The oldest form of literature finds its ideal vehicle in the most modern short modes of communication. Connecting current expressions of the aphorism with its ancient roots is one reason I’ve prepared a new edition of The World in A Phrase: A Brief History of the Aphorism, twenty years after it first appeared.

New aphorists are featured throughout this second edition of The World in a Phrase — from a Roman orator and an Austrian countess to a Harlem Renaissance poet and a Colombian philosopher — encompassing more voices and bringing this brief history up to date. Twenty-six additional aphorists have been added to the original thirty-eight, for a total of sixty-four practitioners through which the history of the form is told.

When the book was first published in 2005, Facebook had only just been founded and Twitter didn’t exist. In the two decades since, the proliferation of social media — which places a premium on brevity, the aphorism’s essence — has created forums in which this shortest of short forms can thrive. Twitter, after all, has the word ‘wit’ in it. An entirely new chapter at the end of the book features those using new platforms to take the form into the future, including meme-makers, street artists, and visual aphorists who mix pithy language with compelling imagery.

Twitter, of course, also has the word ‘twit’ in it and, now known as X, it marks the spot where the unaphoristic reigns, from gauzy inspirational quotes to byte-sized chunks of outrage. This new edition addresses the crucial differences between aphorisms and hot takes and rage posts, and it explores why, especially as generative AI programs like ChatGPT threaten to reduce our cognitive loads to zero, it is essential to our psychological survival to think aphoristically. Aphorisms remain the ultimate deep dives, even in our era of fractured attention spans, when TL;DR has become the catchphrase of a generation.

Kara Walker’s work is part of the millennia-old tradition of the aphorism. Her aphorisms are proof of the enduring vitality of the form and its continuing popularity today. My hope is that this updated edition of The World in a Phrase will be timely and relevant for new readers as well as longtime aphorist aficionados.

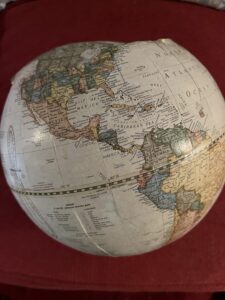

I’m dusting off my trusty old globe in preparation for upcoming talks about The World in A Phrase.

Back in the day, I conducted little happenings with aphorisms in which I neatly excised the Arctic Circle from a desktop globe, so that the top of the earth came off like the lid of a cookie jar. I dropped in dozens of little slips of paper, each one bearing an aphorism — either one I had composed myself or one from another aphorist. I then offered the globe to people and asked them to reach in, pick a phrase from the globe, and read the aphorism aloud. I’ll be conducting the same little happening over the next few weeks after the book comes out on November 10.

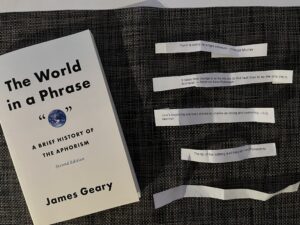

These aphorisms tumbled out when I turned the globe upside down — unselected aphorisms from the last time this happening happened. If someone selected the blank slip of paper during a talk, they could name any subject and I would have to cite an aphorism on that subject. If I didn’t, they got a free copy of the book. If I did, they owed me $19.99!

Receiving the first copies of a book you have written is the oddest feeling… The object before you has lived in your mind for years, and you have spent many days working to place what is inside your mind outside your mind so others can see it.

The book is like a black box at first. What’s inside it? Did I write it? It seems like so long ago. And it was so long ago! Because the wheels of publishing turn slowly. But the grind — the writing, the promoting, the waiting — feels exceedingly fine (eventually).

Then it’s like meeting an old friend you haven’t seen in a long time. At first, you’re not quite sure it’s him — he’s changed a bit and so have you. But then you look again and yes, it’s him! I remember now. I wrote this. How wonderful to see you again!

Please come in. Make yourself at home. Stay awhile.

Have you met my daughter, Hendrikje? I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Through a series of fortunate hyperlinks, I recently stumbled across aphorisms on journalism by John Bennet, former New Yorker editor and professor in magazine writing at Columbia Journalism School. In a brief 2022 obit on the Columbia j-school site, Betsy Morais, editor in chief of the Columbia Journalism Review, wrote that Bennet “often spoke in aphorisms.” Those aphorisms are funny, wise, and profane — just like the best newsrooms.

Put the best shit at the end, the second-best shit at the beginning, and all the other shit in between.

The best journalists always overreport.

Don’t rob the reader of feeling emotions by reacting for them (“I started to cry”).

A writer is a guy in the hospital wearing one of those gowns that’s open in the back. An editor is walking behind, making sure that nobody can see his ass.

Richard Kostelanetz is interested in “radical constraint.” And the aphorism is the ideal form in which to put that interest into practice. Aphorisms are, by definition, short. But Kostelanetz takes concision to an extreme by restricting himself even further — to aphorisms consisting of just four (“quadrigraphs”), three, and two (“minimaxims”) words. Kierkegaard wrote, “The more restricted I am, the more creative I become.” That is certainly true of Richard Kostelanetz’s radically constrained aphorisms.

Four-word aphorisms

If uninvited, arrive late.

Anyone understood becomes predictable.

Three-word aphorisms

Eschew questionable explanations.

Pomposity precedes comeuppance.

Historians repeat themselves.

Leftovers attract vultures.

Publishing amplifies whatever.

Be seriously funny.

Write briefest classics.

Two-word aphorisms

desire desires

never generalize

sentences end

Scroll down on this page to read some of Richard Kostelanetz’s other four-word aphorisms.

I first blogged about the aphorisms of Ninus Nestorović back in December of 2007. Ninus was recently in touch with some new aphorisms, deftly translated by his 15-year-old daughter, Tea. Ninus is a journalist, satirist, and ex-professional footballer who lives in Novi Sad, Serbia. These sayings come from his book 11:52. In an email accompanying the aphorisms, Ninus wrote he believed I would like them — and I do!

To hide from the truth, a person need not stand behind the television, but in front of it.

The poor will leave their children everything they don’t have.

With clean hands you preserve health; with dirty hands, authority.

My city has more churches than hospitals. Were there a God, the numbers would be reversed.

Were the eyes nearer the heart than the mind we’d see differently.

Translated from Serbian into English by Tea Nestorović.

Ashleigh Brilliant, the prolific creator of the drawings-aphorisms he called “Pot-Shots”, died last month in in Santa Barbara, CA. This New York Times obit has a nice summary of his writing career and a selection of some of his best sayings. A piece in the local Santa Barbara outlet Noozhawk has more detailed information on his life. Brilliant started out as a painter rather than an aphorist. His paintings, however, never went over as well as the sharp, slightly loony titles he appended to them. So instead of working on canvas, he made quick pen-and-ink drawings to illustrate his aphoristic captions. “Soon, I was making lists of titles for pictures I had not yet painted,” Brilliant once said. His have been widely published since 1975, appearing on everything from coffee mugs to postcards. Brilliant’s rules for “Pot-Shots” composition were strict: no saying can have more than 17 words (17 is also the number of syllables in a haiku), none can rhyme, no references to politics, and every saying should be easily translated into other languages. He stopped writing “Pot-Shots” when he hit 10,000. Brilliant insisted that his work could only be reproduced with his permission, so I made certain to reach out to him back in 2007 when I included some of his “Pot-Shots” in Geary’s Guide. A very cordial exchange followed, in which Brilliant granted permission for me to include his work in my book. His only question, which he posed with an exclamation mark: Which of his “Pot-Shots” had I chosen?! Here they are, Brilliant’s sayings from a brilliant mind…

Life is the only game in which the object of the game is to learn the rules.

No man is an island but some of us are long peninsulas.

I feel much better, now that I’ve given up hope.

If we all work together, we can totally disrupt the system.

If you’re careful enough, nothing bad or good will ever happen to you.

I could do great things, if I weren’t so busy doing little things.

In order to discover who you are, first learn who everybody else is, and you’re what’s left.

If you can’t learn to do it well, learn to enjoy doing it badly.

Writer, teacher and translator Irving Weiss passed away on June 13. We have Irving to thank for bringing the aphorisms of Malcolm de Chazal into English.

Malcolm de Chazal (Geary’s Guide, pp. 359–361) was an aphorist and painter from Mauritius. I discovered the 1979 Sun edition of Chazal’s aphorisms, Sens-Plastique, by chance in a used bookstore in San Francisco in the mid-1980s. The cover has one of Chazal’s paintings on it — a pair of old shoes. Something spoke to me from the book, as sometimes happens when you encounter a book by someone you’ve never heard of in a used bookstore. I bought it and have been delighted and fascinated by Chazal ever since.

There are only three editions of Sens-Plastique in English, all of them the work of Irving. The latest and most comprehensive is from Green Integer, which also contains the introduction by W.H. Auden, a Chazal aficionado, which Irving arranged for the original 1971 publication of selections from Sens-Plastique.

Irving knew Auden from his college days in Michigan in the 1940s. He and his wife, Anne, lived on the Italian island of Ischia when Auden did. (They are featured in the BBC documentary about Auden, “Tell Me The Truth About Love”; Auden blessed their marriage by dedicating his and Chester Kallman’s translation of Die Zauberflöte to them.)

Irving found Sens-Plastique in the original French on Auden’s bookshelves. “Opening it at random, I was almost immediately struck by what I read, the lightning bolt transforming into, ‘This is what I wd write if I could, so I must translate it,’” Irving wrote to me in an email in 2008.

Irving translated a few pages and found Chazal’s address through Gallimard, his French publisher, and Chazal was delighted with Irving’s work. “We corresponded in French until one day years later he switched to perfect English,” Irving wrote to me, “and I remembered that he had attended Louisiana State University for six years studying agronomy.”

Irving corresponded with Chazal from the 1950s through the 1970s, though the two never met in person. He also published translations from Chazal’s Poèmes and Sens Magique, which are also aphoristic:

A rock needs no burial till it dies.

Eggs are all chin.

Irving told me that Chazal actually considered his Sens-Plastique observations science, not metaphor. That makes sense, given the uncanny precision of the aphorisms…

Light shining on water droplets spaced out along a bamboo stalk turns the whole structure into a flute.

Irving and I connected thanks to artist, author and critic Richard Kostelanetz, who mentioned my books to Irving. Irving did a search online, found this excerpt from a 2008 aphorism talk in which I discuss Chazal and read some of his aphorisms (and get the year of his death wrong; Chazal died in 1981), and then emailed me.

We had a lively email exchange — in extremely large type because of Irving’s failing eyesight! — and I was delighted to learn more about Irving’s relationship with Chazal and Auden and about Irving’s own works, including Reflections on Childhood, an anthology compiled and written with Anne, his wife. (I wrote about Reflections on Childhood here.)

Irving was funny, generous with his insights, and endlessly curious about aphoristics. I am fortunate to have known him, even if only electronically, and am forever grateful to him for introducing me to Chazal, one of the strangest and most original aphorists of all time…

Death is the bowel movement of the soul evacuating the body by intense pressure on the spiritual anus.

The sun is pure communism everywhere except in cities, where it’s private property.

The act of love is a toboggan in which those who are joined become each other’s vehicle.

Objects are the clasps on the pockets of space.

Age adds a pane of glass each year to the lantern of the eye.

Irving signed off all his emails with the phrase, “All to the Good.”